While the crisis in Flint, Michigan is still unraveling, what we know so far has served as a huge reminder that clean water is a) something we take for granted and b) maybe not so clean after all. While the issues behind Flint are being traced to governmental oversight, it remains a fact that many cities across the United States still have a water service infrastructure filled with lead.

This could never happen in Wisconsin, though, right? We could never have lead in Wisconsin drinking water, could we?

Lead in Water is a Deep Problem

Wisconsin is a state rich in character, charm and history. The downside to this, however, is that while many other cities had begun to cease the use of lead pipes by the late 1920s, Wisconsin continued to install them through the 1970s, when the negative health effects of doing so began to seem indisputable.

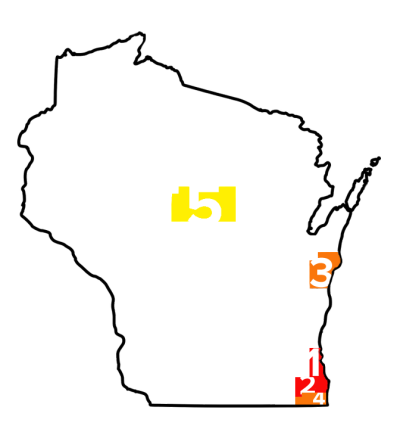

Today, Wisconsin has over 175,000 lead service lines still in use. Opportunities to learn from Flint’s crisis should not be ignored, especially in the following counties where they are most present According to Miguel Del Toral at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, these are:

- Milwaukee County: ~95,000 service lines

- Racine County: ~15,000 service lines

- Manitowoc: ~10,000 service lines

- Kenosha: ~10,000 service lines

- Marathon: ~8,000 service lines

Other counties like Rock aren’t far behind either. The problem of lead service lines in Wisconsin is a big one. To learn more about how lead gets in public drinking water, read our blog How Lead Gets in the Drinking Water.

The prevalence of older homes in the state adds to the problem since many of these older homes have lead plumbing and fixtures. Though only 25-50% of recorded lead is believed to come from fixtures and home plumbing, the presence of antiquated plumbing is not helping this problem.

Federal Legislation on Lead Plumbing

As the negative health effects of lead plumbing became apparent, the United States passed the Lead and Copper Rule in 1991 limiting the concentration of lead and copper allowed in public drinking water, as well the permissible amount of pipe corrosion due to water.

The law has been seen as insufficient for a few important reasons:

- The methods of testing corrosiveness and lead content are unreliable at best. Since many homes feature interior lead piping or fixtures, the testing locations can see a huge degree of variance on their results from one building to the next, even though both are being served by the same water lines.

- Replacing a few lead lines at a time, a response to excessive lead or copper content mandated in the bill, can actually cause a spike in lead levels in drinking water.

A Winning Example

Back in 2001, the city of Madison undertook the controversial process of replacing their lead pipes. Against many strong political opinions, the city put forth a decade long plan to remove the potentially poisonous vessels and replace them with clean ones.

The total cost of the project was about $19.5 Million dollars and, although it began in 2001, had been proposed and spent time in legislative limbo for years before that.

Madison’s rollout is also a subject of praise as they set out on the project fully aware of the dangers that improperly or incompletely replacing the pipes could bring about. The successful completion of this project has made it a model for other communities looking to remove lead pipes from municipal water systems.

Milwaukee may be looking on with enthusiasm and a bit of envy, but the city is also aware the cost of doing likewise. Madison’s $19.5 Million bill for the project, translates into about $600 Million for Brew City to do the same.

Milwaukee Water Works spokeswoman Sandra Rusch Walton understands the high cost is only half of the equation. The legislative nightmare of passing this kind of spending (much of which would come back to taxpayers) is an unprecedented obstacle in the state.

Alternative Solutions

Adding an anticorrosive to a municipal water supply is the most popular way to prevent lead entering drinking water. Flint’s biggest technical problem when they switched to the highly-corrosive Flint River for their water supply was the lack of anticorrosives to prevent the water carrying the interior of the pipes into Flint homes.

Anticorrosives, like orthophosphate, may keep lead levels down (and are federally mandated in some cases), but they are not without their drawbacks. For starters, they promote algae growth and harm water surface quality when they’re sent back into lakes by wastewater treatment. Accelerated algae growth can produce other toxins that now need to be managed.

One of Madison’s top factors in their decision to go the replacement, rather than treatment, route was the goal of preserving the beautiful and abundant lake scenery that surrounds the Capital city.

Steve Elmore, Water Supply Chief for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, believes that Madison’s decision will allow Wisconsin to have a “big part” in the rewriting efforts taking place around the Lead and Copper Rule. Ideally, the law could require municipalities to do a full lead service line replacement, just like Madison.

It may even, at some point, make federal funds available to do so. One thing is for sure, Wisconsin is on the right track. Despite having a history of blindness to the problem of lead service lines, enthusiastic discussion and ambitious action give Wisconsin a clear vision of the future.

A future of clean drinking water.

To request a free home water testing kit, click here.

For more information on Wisconsin drinking water, click here to download our ebook The Wisconsin Water Guide